This week has been a roller-coaster for fans of “Rap’s Most Dangerous Group”: N.W.A. On Monday (June 8), it was revealed that Ice Cube will reunite on stage with DJ Yella for the first time since 1989. MC Ren will be there too as part of Los Angeles, California’s BET Experience. Moreover, according to Cube, Dr. Dre may even bless the stage “If you wish upon a star.” This would make history, and arguably reunite one of Hip-Hop’s most important groups for the first time in more than 25 years—or before YG was even born.

The news felt good to core fans of N.W.A., 15 years removed from an awkward attempt to re-form the group with Eazy-E deceased, Snoop Dogg pinch-hitting, and Yella inexplicably not included. Additionally, as Cube and Dre have been doing the press for August 14’s upcoming Straight Outta Compton biopic, it was a rare opportunity to see Yella and Ren mentioned in any headline.

Coincidentally, that scarcity of inclusion would prove to be a sticking point by Wednesday (June 10). MC Ren—never one to mince words—took to Twitter to lambaste Straight Outta Compton‘s marketing teams for “leaving [him] out of movie trailers” and “tryin’ to rewrite history.” Notably, the MC born Lorenzo “Ren” Patterson criticized Universal Pictures, the film studio. However, Dre, Cube, and Eazy-E’s widow, Tomica Woods-Wright are the film producers. In a group looking to repair some of its wounds 25 years later through a decorated look at trailblazing and legacy, are things getting cyclical? While that answer will prove itself with time, perhaps the more appropriate question is, does MC Ren have a point?

In 2015, Dr. Dre flirts with billionaire status. Ice Cube has gone from AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted to an entertainment mogul. Both men have become Hollywood A-listers. Meanwhile, 20 years removed from his tragic and controversial death, Eazy-E remains one of Rap’s eternal pioneers. The mastermind behind N.W.A., Straight Outta Compton will invariably immortalize Eric Wright as Rap’s hustler-rapper originator, ladies man, and Gangsta Rap visionary. That’s the “big three,” but what about the other two members?

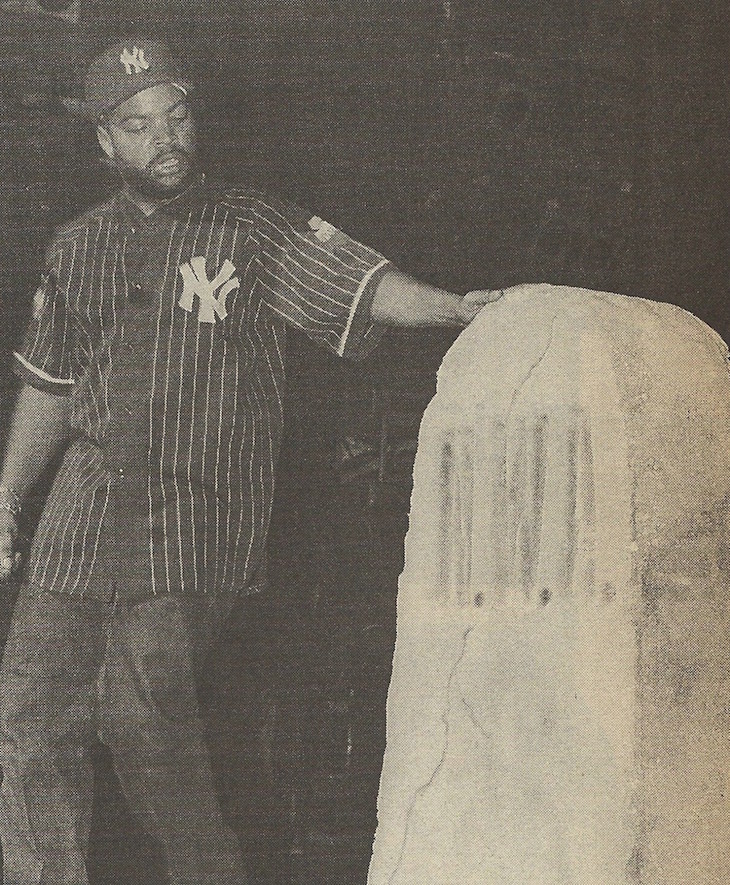

MC Ren may have good reason to be angry. Of the living members of the group, it is Ren who is closest to his roots as the outspoken, street-tough MC from Compton, California. While Cube is remembered as the shining lyricist of Straight Outta Compton (the album), who held down follow-ups 100 Miles and Runnin’ and Efil4zaggin down? On both singles, “Appetite For Destruction” and “Alwayz Into Somethin’,” Ren had the flow, the piercing lyrics, and the attitude that made N.W.A. weather the storm of watching Ice Cube leave, and thrive.

Similarly to an Inspectah Deck or a Khujo Goodie, MC Ren lives in the shadows of some of his band-mates. However, to lovers of lyrics, Ren is revered. He penned his own rhymes, a decoration that at least two of his band-mates cannot fully claim. Moreover, Ren’s fast, sure-handed flows were incredibly innovative for the late ’80s, a time when mono-syllabic rhyme styles were still acceptable. By the early ’90s, Ren’s skills had advanced, keeping up with faster-paced tracks, and winning over N.W.A. fans who could’ve easily dismissed the group as media hype.

“Because the times are so wrong, gotta stay so strong

Niggas gotta keep it goin on and on

And don’t let no paleface throw your ass in a snail race

Have your residence occupyin a jail space

That’s what they want to do cause the system is fucked around

I try to let you know with the records that’s underground” – MC Ren, “Real Niggaz Don’t Die”

Like the Fullback or the Center on a winning offense, MC Ren helped move the ball up the field so many times for Niggas Wit’ Attitude, even if he was often not credited with the score. It was Ren’s political, racial, and religious views that were clearly spoofed in CB4‘s “Euripides” character. Funny in the film, the reality is that Lorenzo Patterson’s Pro-Black messages and public conversion to Islam were critical parts of N.W.A.’s complete makeup. For a group often remembered for spitting in the face of conservative America, MC Ren cemented the front-lines. Undoubtedly, the biopic will examine the fact that five young Black men from South Central, Los Angeles would make the old guard uncomfortable while simultaneously grabbing their children’s eardrums. Was Ren not one of the most antagonistic voices of the group? Or does he eternally play the backseat to the much more media-savvy Cube, despite being in N.W.A. twice as long?

“I said fuck the police but with a little more force

And maybe now I get my point across

It’s a lot here that’s goin on, just open your eyes and look

Everyday a young nigga is took

Off the face of the street by a police

It’s like they gotta a nigga chained on a short leash

You can’t leave out the city that they shacked up

Cause if you do that’s the right they got you jacked up

It’s embarassin because you know they justice, but all you can do

Is say fuck this, because if you move, that’s all she wrote” – MC Ren, “Sa Prize (Part 2)

As media analyzes Ice Cube’s incredibly potent opening lines from 1988’s “Fuck Tha Police” for their timeless effect, dig a little deeper and that credit is easy to share. MC Ren’s mind, pen, and lyrical delivery are elite. But history, and those writing it, can be cruel.

MC Ren’s moves have not been mainstream since N.W.A.’s 1991 disbanding. While 1992 EP, Kiss My Black Azz predated Dr. Dre’s The Chronic, anticipation was already focused on Dre and his skinny protege Snoop Dogg, following 1991’s “Deep Cover.” However, Ren was not playing with a handicap. His DJ Bobcat-produced EP nearly cracked the Top 10, and 1993’s Shock Of The Hour scored a gold plaque, and a #22 debut. Amidst an on-record conversion to Islam, MC Ren was far less marketable to the mainstream, than the 40-guzzling, lowrider-dippin’, locc-wearing counterparts—all images notably included in Straight Outta Compton‘s trailer.

Take away the delivery or the content, and MC Ren is a testament of loyalty to Eazy and his widow. By 1998’s Ruthless For Life, MC Ren was a flagship artist on a label that had faded from glory. Moreover, the N.W.A. alum proverbially wore the chain, even on his last big label album. Suffering through the second half of the 1990s, it was not until ’99’s 2001 reunion with Dr. Dre that MC Ren appeared mainstream again, and arguably tokenized at that. The villain was included in both unofficial N.W.A. records, as well as the Up In Smoke Tour. But after Dre’s tour raked in millions, Cube got a special single, and then promoted Next Friday with a high profile soundtrack single, what next? Without much—save for a couple of DIY releases in the last 15 years, Straight Outta Compton appeared to be the clear answer.

That was definitely the answer for DJ Yella, who stepped out of the music spotlight in the late 1990s. Yella, deeply affected by Eazy-E’s death, made a lone, largely forgettable album, and then stepped to the front door. Mention DJ Yella to most novice Rap fans, and they’ll usually tell you about porn. Antoine Carraby has, in fact, produced and directed XXX—lots of it, reportedly 300 titles. However, because N.W.A. did not feature scratching to the extent heard by groups like Run-DMC, EPMD, or Stetsasonic, his accomplishments are often downplayed. Yella didn’t brandish guns in interviews, or pop out lenses from his glasses, he barely said anything. However, like the shyer days of DJ Premier in Gang Starr, or Terminator X in Public Enemy, he spoke with his hands.

As Dr. Dre is commonly associated with a studio ensemble at his side (Daz Dillinger, Scott Storch, Sam Sneed, DJ Khalil, Mel-Man, Warren G), DJ Yella may have been the first. Together, the Compton kids got their start in World Class Wreckin’ Cru—a group that history has not embraced. However, when street impresario Eazy-E wanted sounds for his foray into Rap music, Dre and Yella were who he sought out. Both men helped drive Dance hits for the Electro group who later scored Epic Records backing. Yella was twisting the studio knobs with Dre. He was credited with Rapped In Romance‘s sampling, drum programming, scratching, and mixing, right alongside Dre.

At Ruthless, Dre and Yella had a formula. Cube’s separation from N.W.A. brought attention to the group’s sonic prowess—something Cube was going to be unable to replace. In that discussion, Dre stepped up as the face of G-Funk, clever sampling, and those deeply orchestrated street anthems that made Niggas Wit’ Attitude sound mighty. But where did Dre’s craftsmanship begin and Yella’s end? Both men would supply The D.O.C., J.J. Fad, and Michel’le with acclaimed music. Yella and (questionably) Eazy-E produced Bone Thugs-N-Harmony’s first hit, “Foe tha Love of $” three years removed from Dre’s departure. With Yella, Eazy-E also produced his last works. But in crediting Dre’s early sounds, to quote Jay Z, “where’s the love?”

DJ Yella has not spoken out against Straight Outta Compton, or its trailers. The CPT native has stayed true to his 1980s self: mostly quiet, but present. As there are grumblings about potential soundtrack work prompting reunions, perhaps Dr. Dre and DJ Yella’s reunion behind the track-boards is as exciting as the three MCs. Before that though, could a film share the credit—like those N.W.A. liner notes—that the mainstream never did?

Nobody wants to be Ringo Starr, or Tito Jackson. There’s the fourth or fifth man in all things. In the case of N.W.A.’s Straight Outta Compton biopic, the film has many presumed motives. This film is a chance to make a public armistice between Dre, Cube, and Eazy-E—stepping over “No Vaseline” and “F Wit’ Dre Day.” This film is presumed to place blame on Eazy-E’s business partner Jerry Heller for Cube’s exodus, and vilify security guard-turned-mogul Suge Knight for Dre’s exit two years later. Whether or not those portrayals are accurate or fair will remain in debate, as Knight’s on-set antics could cost him his freedom for the rest of his life. But will the film identify the two N.W.A. members who stood beside Eazy, who never left the group, and arguably took a lesser road to stay the course of authenticity? Straight Outta Compton is a prime opportunity to show four men from Compton, California—and South Central’s Ice Cube together, in spirit, celebrating what they’ve built. A trailer is just that—a trailer. Let’s see if the the film tells the full story of the world’s most dangerous group…all of them.

Everybody working in the marketing department for the NWA movie should be fired!!!!! #incompetence

— MC REN (@mcrencpt) June 12, 2015

Related: MC Ren Gets Ruthless About N.W.A. “Straight Outta Compton” Trailers